Business

A Detailed Look At The Notorious Stock Market Crash Of 1929

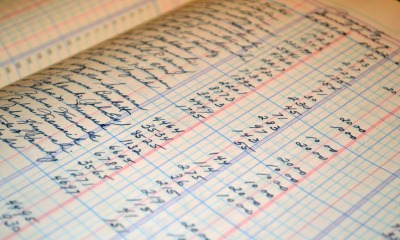

Between October 28 and 29, 1929, the U.S. stock exchange began an unprecedented freefall in value that resulted in it reaching its lowest point ever, just 41.22, on July 8, 1932. This marked the beginning of the Great Depression in the United States, which lasted until the post-war economic boom starting in 1946. During the two day trading period in October 1929, the market lost 23.6 percent of its value. By July 8, 1932 the total market value lost was 89.2 percent.

During the period after the day that came to be known as “Black Tuesday” there were rampant rumors of Wall Street executives and bankers leaping to their deaths from their office windows amidst their losses. This urban legend started almost immediately; Will Rogers quipped the next day that speculators “had to stand in line to get a window to jump out of”. However, the rumors of mass suicide amongst bankers were largely unfounded–though the news was grim, fewer suicides were reported than the urban legend would have us believe.

What Events Precipitated the Stock Market Crash of 1929?

Prior to the events of October 29, 1929, the U.S. stock market was highly unregulated. A huge income and wealth disparity existed between rich and poor. 32 percent of the country’s wealth was held by 0.5 percent of the population, even after efforts in the early 1900s by President Theodore Roosevelt to break up the large corporate trusts that controlled commerce. The stock market reached a high of 381.17 on September 3, 1929 before beginning its descent on October 28th, opening at 295.18 and closing for the day at 260.64.

Much has been written about the causes of the crash, but few pinpoint earlier signs of weakness in the market as warning signs of impending doom. On Monday, March 25, 1929, the market lost 3 percent in value, falling from 306.21 to 297.50. Two days later the National City Bank infused $25 million in capital to help stop the slide, though this action did little to delay the oncoming crash. Interestingly National City Bank head Charles Mitchell, who sat on the Federal Reserve Board, was called on to resign by Senator Carter Glass of Virginia. Glass would later author the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which separated investment and commercial banking operations and established the FDIC.

Extension of Credit and Troubling Economic Signals

Although the credit infusion of March 25th helped put the market back on track, the relatively novel idea of extending credit to customers who couldn’t pay all at once, and the over-borrowing that took place as a result, were symptoms of a larger problem. Industrial output was down in 1929 and consumer purchases were fueled by easy credit. These factors, combined with the under-regulated market on Wall Street, helped to accelerate the eventual crash.

Impact of 1929 Stock Market Crash

The market attempted to rebound on October 29, but to no avail. By the autumn of 1930, and continuing through 1931 and 1932, the market had plunged severely, taking with it much of the wealth that had been created during the “Roaring Twenties”.

The Pecora Investigation, established by the U.S. Senate in 1932, investigated the crash and released its findings in 1934. In the 400 page report, banking practices detrimental to consumers were exposed. In addition to the Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall), Congress passed several pieces of important legislation to address the practices and ethical conduct of investment and commercial banks. Many of these laws remain on the books today in the hopes of preventing another cataclysmic crash.

Byline

Francis Bergstrom is intimately familiar with the financial world and knows how critically important it is to make sure the finance sector is filled with competent, responsible professionals. Those who’d like to make a contribution toward this end should check out the financial planning jobs with moneyjobs.com.

Image credit goes to filipebarreto.

-

Tech11 years ago

Tech11 years agoCreating An e-Commerce Website

-

Tech11 years ago

Tech11 years agoDesign Template Guidelines For Mobile Apps

-

Business6 years ago

Business6 years agoWhat Is AdsSupply? A Comprehensive Review

-

Business10 years ago

Business10 years agoThe Key Types Of Brochure Printing Services

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoWhen To Send Your Bulk Messages?

-

Tech5 years ago

Tech5 years ago5 Link Building Strategies You Can Apply For Local SEO

-

Law5 years ago

Law5 years agoHow Can A Divorce Lawyer Help You Get Through Divorce?

-

Home Improvement6 years ago

Home Improvement6 years agoHоw tо Kеер Antѕ Out оf Yоur Kitсhеn